Legal BlackBook

TM

CyberInsecurity

April 2018

CYBERSECURITY IN THE NEWS

The Tipping Point?

How will we know when cybersecurity has become a household word, a genuine phenomenon? Not by the number of law review articles on the subject, or even the number of Big Law practice groups devoted to it. It’s more likely to be revealed by an unexpected event in the popular culture.

Would this qualify? In September, Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. will roll out its first cybersecurity badges that scouts can earn by demonstrating their mastery of the subject. It’s part of an effort to boost girls’ interest in tech, which in turn could lead to their greater representation in the field.

Read more from NBC News.

What’s the definition of education? A pretty good one, when you think about it, is the ability to change.

Now wrap your mind around this. According to a recent report by CyberArk,

46 percent of organizations never change their cybersecurity strategy even after they suffer a cyberattack.

And only 8 percent of the security professionals surveyed said that their company continuously conducts penetration tests to determine where their vulnerabilities

are located.

These numbers suggest that, where cybersecurity is concerned, some of the pros companies depend on may need to be sent to reeducation camp.

Read more in TechRepublic.

Collaborating for Security

Continuously Test

Never

Change

A few years ago, Siemens was immersed in a bribery scandal. In the wake of it, as the company took major steps to reform, then-General Counsel Peter Solmssen reached out to his company’s competitors, and they agreed to cooperate to combat not just bribery but the competitive advantage it had offered. Solmssen called this joint effort the Cabal of the Good.

Flash forward. In February, Siemens and seven of its competitors signed what they called the Charter of Trust, vowing to cooperate in order to enhance cybersecurity worldwide. It’s actually even more ambitious than this may sound. It calls not only for the cooperation of the eight companies (the other seven are Airbus, Allianz, Daimler Group, IBM, NXP, SGS and Deutsche Telekom), but also governments.

Read more in AutomationWorld.

The First Cybersecurity Style Guide

The Bishop Fox Cybersecurity Style Guide, published in February, is billed as the first of its kind. Hacker lexicons have been published, but never one dedicated to cybersecurity, according to lead editor Brianne Hughes.

It aims for breadth rather than depth, and it does a good job. In 92 pages (including preliminary notes, appendices and an epilogue) it’s got everything from AI to zero day, and it’s almost guaranteed that you won’t know them all.

One warning: it’s designed for security researchers. That means there’s an emphasis on proper usage. Many of the words listed are not defined. This can be annoying for a more general audience, and a missed opportunity for the editors. (The appendix does include links to other guides that fill in the gaps.)

There’s one particularly nice feature. If you like it, you’ve got it. You can download it simply by clicking here.

Read more on The Parallax.

A Company’s Cybersecurity Information

May Not Be an Open Book

Still, two weeks later Republican Governor Rick Snyder signed the bill into law.

46%

8%

When Will They Ever Learn?

Let’s say your company just discovered it’s suffered a data breach. The CEO asks whether it should be reported to the state police. As the general counsel, you feel it’s clearly information that’s going to have to be disclosed within a few months, and you point out that the police may help the company counter the attack.

But your boss isn’t happy. The company has been struggling lately. “This would be a lousy time for this to get out,” the CEO complains. And what if the media catch wind and file a Freedom of Information Act request with the police?

This isn’t purely hypothetical. The issue has come up, and in March Michigan’s Legislature overwhelmingly.

Predictably, the vote was not greeted warmly in the media or by the media.

May 2018

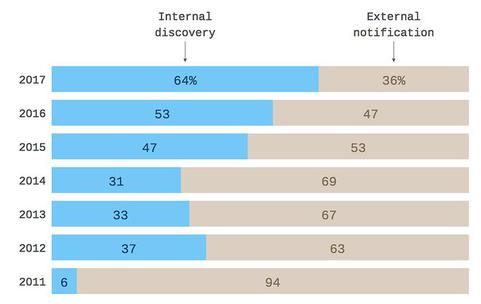

We’re Getting Better at

Tired of reading depressing articles about cybersecurity? They always seem to feature statistics that go from bad

to worse.

But new data suggests that we’re actually getting better at cybersecurity. These are the kinds of statistics we’ve been waiting for.

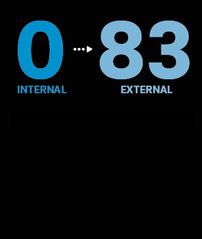

Last year in North and South America, 64 percent of security breaches were discovered by the victim companies themselves rather than external sources like law enforcement, according to Axios (citing Mandiant’s M-Trends 2018 report). That’s quite a contrast to the results in 2011, when only 6 percent of breaches were discovered internally.

Axios didn’t mention another positive statistic that’s even more startling. This one can be found in the 2018 Trustwave Global Security Report. Looking at the length of time it takes to discover compromised data from the date of intrusion to the date of detection, the report found that for intrusions detected internally, it was zero days—meaning on average they were detected in less than one day. For the incident to be reported externally, they averaged 83 days.

So, companies must be doing something right. Maybe more things than they get credit for.

Read more from Axios.

Median number of days between intrusion and detection for detected incidents

INTERNAL EXTERNAL

Cyber Detection

Arizona’s Surprising Coice to Manage Cybersecurity

Here’s a development that’s going to be watched by state administrators around the country. Arizona made a bold move to protect itself from cyberattacks.

The state has 133 agencies in all. That’s a lot of data to worry about.

And it knows it has vulnerabilities because it was hacked during the last national election.

The solution? It decided to hire a single firm to handle cybersecurity for all of them. And it didn’t even choose an Arizona company. It picked RiskSense, based in neighboring New Mexico.

Interestingly, one of the prime reasons it cited was the ease of using the vendor’s software. It scores an agency’s cyber vulnerabilities with a system modeled on credit ratings, so someone without an IT background can quickly see how each is doing.

Read more from StateScoop.

Don’t Leave Cybersecurity to IT

Elizabeth Denham

You can’t rely on your information technology team to protect your company from data breaches. That’s the message that the United Kingdom’s information commissioner delivered in her keynote address in April at the National Cyber Security Centre's CYBERUK conference in Manchester, according to ZDNet.

"Security is a boardroom-level issue,” Commissioner Elizabeth Denham told the audience. “We have seen too many major breaches where companies process data in a technical context, but security gets precious little airtime at board meetings."

And failing to hire specialists and to properly invest in security is a recipe for disaster, she said. Denham cited companies that paid a steep price for their

security failures in last year's WannaCry attacks.

Recent revelations about Facebook and Cambridge Analytica were a “wake-up call” about the importance of protecting data, she added.

Read more from ZDNet.

Does a Nonprofit Need Cyber Insurance

Nonprofits typically don’t have a lot of extra money to spend. And they don’t figure to be the kinds of targets for cyberattacks that large data-rich (and just plain rich) companies can be. So, how much time and money should they spend on cybersecurity?

It’s a good question. And it’s answered with intelligence and clarity in an article that appeared in NTEN, which stands for Nonprofit Technology Network.

The article discusses insurance, but it doesn’t have an agenda and it isn’t pushing any particular solution. It advises readers how to think about the risks of their own work environments in order to make prudent decisions for their own companies’ needs.

The courts have been waiting for the law to catch up with technology for a long time. But given the warp-speed of tech advances and the almost nonexistent pace of legislation these days, not many big cases have been mooted by new laws. But one was in April.

And it was a big one. It was a case that had made it all the way to the Supreme Court. It was Microsoft’s cloud case, which began in late 2013.

As you’ll recall, federal agents had obtained a warrant seeking access to the email account of one of the company’s users. The warrant was issued on a showing of probable cause that the email contained evidence of drug trafficking. But Microsoft declined to provide access, arguing that the data was stored on servers in Ireland, and the law did not reach overseas.

The long-running litigation and the attendant publicity finally led to legislative action. The Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act passed in March, and it requires companies to turn over data under these circumstances, no matter where it’s stored.

The feds got a new warrant to replace the old one, and the Supreme Court, finding that there was no longer a live dispute, sent it back to the district court with instructions to dismiss.

If you’ve been holding your breath, you can exhale now.

Supreme Court

Drops Microsoft

Case

June 2018

Welcome to summer, prime hacking season. If that sounds like a downer, it doesn’t have to be. It’s a warning, and there are measures you can take to avoid having data stolen.

The most important factor is your mindset. If you let down your guard, and many summer travelers do, you’re vulnerable.

Vacationers often conduct business on personal devices, and they use WiFi connections, such as those in airports, that are not secure. Or they check business email in hotel office centers equipped with computers that are equally unprotected.

What they don’t realize is that cyber criminals are often lurking nearby, waiting for these opportunities to steal data,

which they can accomplish in a matter of seconds.

Read more from foxbusiness.com.

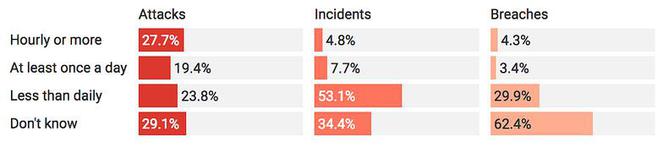

Local Governments Are Overmatched

by Cyberattacks

Source: University of Maryland, Baltimore County Get the data

In recent weeks, two major American cities had services disrupted by cyberattacks. A hacking attack in Baltimore disrupted online emergency dispatch services for nearly a full day. And Atlanta was hit with a ransomware attack that took city services offline for nearly a week.

These are the kinds of events that grab public attention, but research has suggested that the problem

is far larger than a few isolated events.

Local governments across the country are unprepared to prevent cyberattacks, and furthermore, they never identify who was responsible for the majority of those they detect, the research found.

Nearly half of those surveyed said they are attacked daily, but most don’t even record all of them.

The biggest impediment to improving cybersecurity is that local leaders have not made it a priority and have not demonstrated sufficient support for the IT and cybersecurity officials who filled out the survey.

Read more from theconversation.com.

NIST Updates its Popular Framework

Credit: N. Hancek/NIST

In April, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released version 1.1 of the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure

Cybersecurity. It was an update of the first version of the voluntary guidelines NIST published four years ago at the direction of the Obama administration.

The organization announced these changes to the original:

Version 1.1 includes

updates on:

• authentication and identity,

authentication and identity,

• self-assessing cybersecurity risk,

self-assessing cybersecurity risk,

• managing cybersecurity withinthe supply chain and

managing cybersecurity withinthe supply chain and

• vulnerability disclosure.

vulnerability disclosure.

NIST also included a brief description of its methodology: “The changes to the framework are based on feedback collected through public calls for comments, questions received by team members, and workshops held in 2016 and 2017. Two drafts of Version 1.1 were circulated for public comment to assist NIST in comprehensively addressing stakeholder inputs.”

Cybersecurity Tips for

Summer Vacations

A New Model for Cybersecurity Investigations

Paul Rosenzweig

Shouldn’t someone investigate cybersecurity events to determine what happened, and how similar incidents might be prevented in the future? And with no effort to cast blame or judge whether the savings would justify

the cost?

There is an agency that already performs this function when there’s a plane crash: the National Transportation Safety Board. Why not use the NTSB as a model for an agency that would be tapped to investigate major cyber breaches?

This was the suggestion of Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute in Washington, D.C., who wrote a paper endorsing the idea, which he credited to Representative Denny Heck (D-Wash.). Rosenzweig, who also manages a small consulting company on cybersecurity and teaches at George Washington School of Law, suggested the new agency might be called the Computer Network Safety Board.

Read more from insidesources.com.

White House Axes Cybersecurity Czar

In the 1960s, some writers of fiction publicly complained about the difficulty they had plying their craft because they found it impossible to compete with the reality they were confronted by each day.

There are undoubtedly novelists today who feel the same way. But these days even journalists are finding themselves stretched in unusual ways. It can sometime be difficult to reconcile the competing realities we’re confronted by. And these can involve realities that bump into each other not only in different areas of the news, or different events, but sometimes even in the

same stories.

So, we have grown used to reading about the ever-expanding challenges of fending off cybersecurity risks. And preparing for the next new assault. And government agencies have tried hard to reassure businesses that they are doing everything they can to work with them against this growing threat.

And yet, at the very time that the Department of Homeland Security, which is generally viewed as the lead agency in defending against cyberattacks, was talking about the expanding risks, the administration eliminated the position of Cybersecurity coordinator on the National Security Council because

the role was no longer necessary.

Read more from csoonline.com.

If you are interested in contributing thought leadership or other content to this platform

please contact Patrick Duff, Marketing Director at 937.219.6600