Legal BlackBook

TM

CyberInsecurity

I

T

I

JUNE 2018

When Will We

David Hechler, Editor-in-Chief

CYBER SURVEY

The ACC report is packed

with sobering comments and statistics, and little

to console its members.

n May, the Association of Corporate Counsel (ACC) Foundation released its “State of

Cybersecurity Report: An In-House Perspective,” which conveys the results of the organization’s far-ranging survey on this topic. In addition to the statistics elicited from 617

in-house lawyers (based in 33 countries), the report also includes many comments from the respondents. Amar Sarwal, ACC’s chief legal officer and senior vice president of advocacy and legal services, agreed to dig into the data and help us understand what it tells us.

Legal BlackBook: When did the Association of Corporate Counsel first start releasing cybersecurity reports, and how many have there been (including the one you’ve just put out)?

Amar Sarwal: ACC released its first global cybersecurity report in 2015, responding to heightened interest from our members and their stakeholders. This year’s edition is the second in the series. On the basis of these reports, ACC has now conducted two Cybersecurity Summits, and it has weighed in on the advocacy front as well. And, given the significant burden that data security issues impose on day-to-day in-house practice, ACC is likely to do quite a bit more.

LBB: This report is full of interesting statistics. What statistic surprised you the most?

AS: According to the feedback from our in-house counsel respondents, boards of directors don’t seem to be requiring updates on cybersecurity issues as regularly as prosecutors and regulators would prefer. Government officials and other stakeholders believe that more board involvement would ensure that the pressing need for data security would be more effectively addressed. In my view, the jury is out as to whether that sort of top-down approach would work, but there’s little doubt that regulatory officials at every level have been insistent about boards taking closer hold of the reins.

LBB: If you were a new general counsel at a small to midsize company, what would you focus on first, as you assessed your new company?

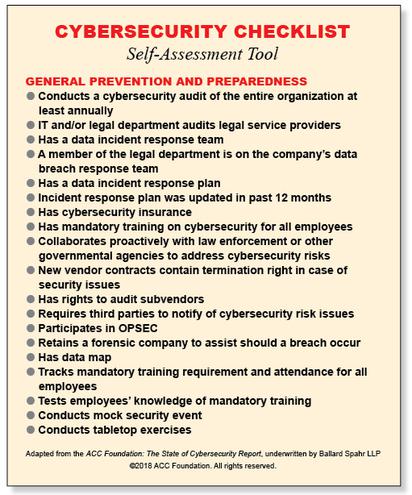

AS: On page 28 of the Executive Summary, the report provides a self-assessment tool that canvasses the various best practices in the cybersecurity arena. Ensuring that your new company has made the necessary investments on those fronts is quite critical. Otherwise, your first few years at the organization could get a bit hairy.

Amar Sarwal

INTERVIEW: AMAR SARWAL /

CYBERSECURITY

IN THE NEWS

Kimberly Peretti

By David Hechler

A

If you are interested in contributing thought leadership or other content to this platform

please contact Patrick Duff, Marketing Director at 937.219.6600

UNDERSCORES

LAWYERS

ASSOCIATION OF CORPORATE COUNSEL (ACC)

We’re still

in the early stages of this epidemic.

Our enemies are far more nimble than companies or governments.

Government officials

and other stakeholders need to end their more adversarial approach

and instead recognize that we’re all in this together.

LBB: If you were an experienced general counsel at a large corporation, what would grab you?

AS: The same self-assessment tool should benefit large companies as well. That said, highly regulated companies have pressures up and down their supply chains that go way beyond that tool, which would be considered table stakes in their world. Even so, large companies should be quite concerned that smaller and midsize companies aren’t as far along as they need to be—at least with respect to what most consider to be leading practices.

LBB: If I asked you to pick a few statistics that seem to capture the reality we’re facing right now in this area, which ones would you choose?

AS: Three in particular come to mind, none of which should be surprising to your readers, but all of which serve to underscore the importance of the issues you cover. First, one in three respondents indicated that either their current company or a previous employer had experienced a data breach, which likely understates the true number of breaches, as many victims have little idea that bad actors have been successfully penetrating their defenses. Second, amidst this onslaught, two-thirds of in-house counsel expect to see the legal function’s responsibilities in the cybersecurity sphere to increase over the coming years.

I’m not sure that it’s a good idea to rely too much on legal—and, in fact, one could argue that the growing effort to do so is a reflection of the inability to solve the problem otherwise. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that many companies expect their general counsel to understand access control mechanisms as well as they might understand how to shepherd an important business transaction or regulatory investigation. Finally, and fortunately, hand in hand with this increased responsibility is an expectation by two-thirds of respondents that budgets devoted to cybersecurity issues will increase over the next year. Of course, more resources are certainly necessary, but companies should take care not just to throw money down rabbit holes.

LBB: Do you see grounds for optimism in any of the survey’s findings?

AS: Thanks for the great question, he mumbles sarcastically. While I generally agree with Andy Dufresne, who reminded us in “The Shawshank Redemption” that hope is a good thing, I think we’re still in the early stages of this epidemic. Our enemies are far more nimble than companies or governments. It will take a sea change in attitudes or approaches on a variety of fronts to make me more optimistic—a sea change that’s simply not reflected in our report, or any other of which I’m aware.

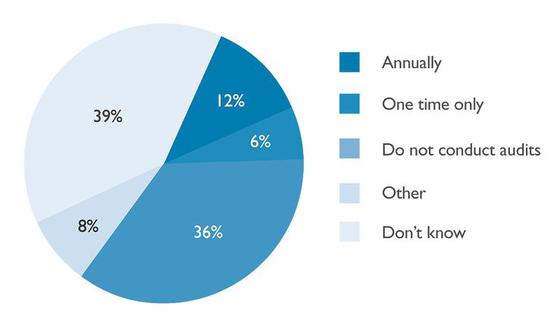

LBB: One statistic that was surprising and disturbing was the number of times respondents chose “don’t know.” It was understandable—even predictable—that they would choose this for many questions about the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation. And they did. But overall, 25 percent also answered that they don’t know if third-party vendors are generally required to cooperate with them during investigations of cyber incidents [p. 81]. And 39 percent don’t know if their company conducts security audits of vendors [pp. 23, 82]. What do you make of this?

AS: Great point! It’s a constant, and disturbing, theme in this report that can be somewhat explained by the fact that not all legal departments are involved in assessing, monitoring or addressing cybersecurity risks and threats. Instead, their companies expect other functions to take the lead, to the exclusion of legal. Either way, it’s simply not a good thing in this environment not to know the answer to those questions.

LBB: You also included lots of interesting comments from respondents. Which three did you find most noteworthy in response to the question “What is the most important thing you wish you had known before the breach that you know now as a result of your experience?” [p.88]?

AS: The comments are quite enlightening, generally conveying the sense that companies are not yet fully equipped to deal with these issues, particularly in terms of how the organization is structured or designed, but also in understanding how to deal with the actual nature of the threat. Though there are many, three noteworthy comments would include the respondent who noted that her client had a policy prohibiting the use of unencrypted drives but had never audited for compliance; the respondent who mused that ex post fines were 10 times the amount of what would have been effective ex ante measures; and the respondent who reminded us how difficult it can be to get senior leadership to understand the underlying issues and devote adequate time and resources to addressing them.

LBB: What were some other comments you found particularly revealing?

AS: One of the most powerful comments in the report comes from a respondent who wishes that the Secret Service had informed them of the breach more contemporaneously, rather than almost two years later. That respondent quite appropriately suggests that the company would have been able to mitigate the harm, had it known sooner. Government officials and other stakeholders need to end their more adversarial approach and instead recognize that we’re all in this together. Of course, punish the bad actors—those companies that don’t even meet a minimum level of preparedness. But it is also important to find ways to support good companies that are trying to do their best.

Beyond that useful reminder, there were many, many comments about the importance of employee training. And, to a point, I agree—modern professionals need to be cognizant of data security risks. But I think it is grossly optimistic to expect training to yield a significant impact. Most employees have far too much on their minds to keep the latest and greatest in phishing attacks front and center. Instead, organizations need to deeply understand how information flows within their business model and ensure that there are impenetrable guardrails around those flows.

LBB: On June 1, you will be leaving ACC after an eight-year run. As you consider the challenges that general counsel have faced during your tenure, where does cybersecurity rank? Is it among the more demanding risks that have confronted them?

AS: Maintaining the confidentiality of important customer, employee or commercial information definitely ranks at or near the top of challenges that general counsel have faced. That said, I’m not a big fan of the hype machine. Over the past two decades, general counsel have been confronted with multiple instances of fraud that go to the heart of the underlying businesses or the apparent difficulty in navigating the international business environment without violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, among many, many other things. It’s never really been an easy job.

As for myself, going forward, I will be a stay-at-home dad with my five children. Also not an easy job.

WORKING WITH

Four tips that companies should follow to maximize

the benefits.

By Kimberly Peretti

THE GOVERNMENT

AFTER A BREACH

A company must be prepared not only to understand the nuances of

working with law enforcement in the aftermath of a breach, but also

to work with

other arms of the government that are likely to

become involved.

he scope and frequency of security incidents continue to grow, as does the media and government attention to breaches.

Different arms of the government continue to actively engage in this space, though they can have varying purposes and agendas. These range from investigating criminal actors behind security incidents, to providing threat intelligence, to sharing information with the broader public to enforcing violations of regulations and laws.

Some government agencies are eager to work with companies that have suffered breaches. This past January, FBI Director Christopher Wray said at a cybersecurity conference: “At the FBI, we treat victim companies as victims.” Wray was encouraging companies to report cybercriminal activity and partner with his agency. But federal law enforcement is only one arm of government that a compromised entity may engage with after a data breach. Others have different mandates and goals.

As a company wades through the mass of decisions required when responding to a security event, it is important to understand in advance the different agencies that it may interact with. It’s wise to be familiar with their agendas, which may or may not coordinate (to the benefit or detriment of the company), and what protections are available when providing them with sensitive and confidential information. Understanding these factors in advance, rather than during a live-fire incident (which many breach responses can be), will go many miles in helping a company navigate the full lifecycle of incident response.

Law Enforcement

Generally, law enforcement’s primary function when they investigate cyber intrusions and data breaches is no different than when they investigate physical crimes: They gather evidence in order to identify, apprehend and prosecute criminals. Cyber crime is unique, however, in that digital evidence is particularly volatile, and cyber criminals can more easily obfuscate their identities and hide their tracks and behavior. Since a company’s investigation often happens first and is more likely to preserve volatile data, law enforcement will often rely on shared information from victims rather than expend their own limited resources.

There are other differences as well. Law enforcement’s role has evolved to include collecting and sharing threat intelligence with companies to help improve overall cyber defense. Since law enforcement gathers data about attackers from a number of different sources, they are often able to share the information that they learn both with victim companies experiencing a breach and through publicized alerts. This evolution is a significant development in the short history of cyber crime, and its importance cannot be overstated. A prime reason for victims to reach out to law enforcement is to gain valuable intelligence on the threat actors behind the intrusion.

Law enforcement also addresses national security investigations, especially as state-sponsored cyber attackers blur the line between traditional criminal and national security incidents. In contrast to a criminal investigation, a national security investigation’s primary focus is often on gathering intelligence about a threat actor. Rather than press for an indictment, law enforcement may seek the most recently available indicators of compromise for an attacker, which can better identify and mitigate attacks. Other national security goals of a cyber investigation may include disrupting the infrastructure used by the actors, which often involves partnering with the private sector.

It’s important to remember that there are many different branches of law enforcement, including state, local and federal agencies. Each has its own jurisdictional boundaries and may have limitations (resources or otherwise) that factor into whether it would be an appropriate entity to investigate any particular cyber crime. The Department of Justice’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section provides a chart to help companies identify which law enforcement entities to contact, depending on the type of incident.

Other Government Authorities

A company must be prepared not only to understand the nuances of working with law enforcement in the aftermath of a breach, but also to work with other arms of the government that are likely to become involved, particularly if an incident becomes public (e.g., through formal legal notification, popular press or other means). Two groups of government authorities in particular come to mind.

First is the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which serves as a kind of cyber intelligence information clearinghouse. Whether through the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team or through partnership with law enforcement or regulatory entities, DHS receives and collects cyber threat intelligence that it then shares with the rest of the public and government. Under the authority of the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act, DHS, through the department’s National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center, maintains the Automated Indicator Sharing portal for receiving and sharing cyber threat indicators with participating companies. Note, however, that the goal of this program is to share as many indicators as quickly as possible, so DHS does not validate those shared through the portal. When possible, though, DHS does assign a reputation score to specific indicators.

Second, and of course on the mind of any company in the midst of a breach response, are regulatory agencies. In contrast to law enforcement, regulators generally are most focused on protecting consumers. They also have, as a primary agenda item, compliance with applicable laws and regulations. On the federal level, there are both general and industry-specific regulators, including some with overlapping jurisdictions. For example, state attorneys general and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have general oversight authority and similar/overlapping jurisdiction. Since any individual incident can result in inquiries from one or more of these regulators, it is important for companies to know which regulators may investigate them and how to coordinate any such investigations.

The FTC actively investigates security incidents under its Section 5 enforcement powers to determine whether companies’ security practices were deceptive or unfair to consumers. State attorneys general receive breach notifications and may publicly post information about incidents, up to and including the full notices themselves. One or more attorneys general may also conduct their own investigations into a breached company’s practices, up to and including bringing cases and seeking fines for failure to comply with state and federal laws.

In contrast, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights reviews and investigates notices from breached entities and complaints from consumers and conducts regular audits of HIPAA-regulated entities. Both the FTC and state AGs can similarly investigate incidents involving HIPAA or health-related information. These are good examples of overlapping jurisdictions on both the state and federal levels.

For companies to assess how to coordinate a multitude of regulatory investigations, it is important to understand overlapping jurisdictions and which agencies may not share information or coordinate in the wake of a breach. Knowing that law enforcement and regulators do not operate as “one united government” and rarely exchange information among themselves in the wake of an incident is often relevant in deciding whether to report to law enforcement. Indeed, this has been a long-standing concern of companies, and even prompted FBI Director Wray in March to reiterate that the FBI treats victims as victims, and that the FBI does not believe that it has a responsibility, after companies provide it with information, “to turn around and share that information with some of those other agencies.”

Practice Tips

Since involvement with government authorities is more a “when, not if” question, it is important for companies to plan for those interactions before an incident occurs. Below are four tips they should consider when anticipating working with the government.

1) Establish an Early Relationship

Establish an Early Relationship

The better the communication between a company and the government after a security incident, the more likely that the relationship will be positive for both parties. With that in mind, the Department of Justice recommends establishing relationships with law enforcement before an incident occurs. Opening lines of communication before a data breach allows faster and clearer communication between the parties in a crisis.

2) Understand Each Arm of the Government’s Purpose and Agenda

Understand Each Arm of the Government’s Purpose and Agenda

Understanding the purposes and agendas of different arms of the government can inform the company’s interactions with them. The facts of the particular incident will influence both which agencies become involved and what goals those agencies will pursue. Anticipating those agendas can help a company prepare better communication and response plans.

3) Understand the Different Options and Protections for Sharing Information With the Government

Understand the Different Options and Protections for Sharing Information With the Government

When working with the government, companies have a variety of methods for sharing information. For federal law enforcement conducting a criminal investigation, companies may want to request a formal legal process before sharing information that has privacy implications. Information that a company shares with law enforcement is protected under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure when provided pursuant to a grand jury subpoena, for example. Sharing information this way can also avoid potential conflicts with the Electronic Communications Privacy Act and demonstrate a general commitment to the privacy of the individuals whose personal information the company holds. Recall also Wray’s reminder that, at least in the eyes of the FBI, information shared with law enforcement need not be passed along to regulators.

Companies that do share information with regulators should consider exploring whether an applicable Freedom of Information Act exemption is possible. An exemption can mitigate the risk that sensitive data shared with a regulator will become public knowledge.

4) Understand How to Have a Coordinated Approach to Working With Different Arms of the Government

Understand How to Have a Coordinated Approach to Working With Different Arms of the Government

Since the various arms of government often have overlapping authorities and agendas, it is important to coordinate communications with them. Wherever possible, a company subject to multiple inquiries from different arms of the government, in particular various state and federal regulatory agencies, should identify whether a coordinated response is possible and in its interest. A well-coordinated response will incorporate all of the previous points to maximize the benefit to the company while minimizing the risks.

Kimberly Peretti is a partner and co-chair of Alston & Bird’s Cybersecurity Preparedness and Response Team and National Security and Digital Crimes Team. She is the former director of PwC’s cyber forensic services group and a former senior litigator for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section. She draws on her background as both an information security professional and a lawyer in managing technical cyber investigations, assisting clients in responding to data security-related regulator inquiries, and advising boards and senior executives in matters of cybersecurity and risk. Peretti is a Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP).

INTERVIEW: BART HUFFMAN / REED SMITH

CULTURE SHIFT, COURTESY OF EUROPE

The GDPR will change the way that companies process data.

B

Bart Huffman

for Summer

Vacations

Welcome to summer, prime hacking season. If that sounds like a downer, it doesn’t have to be. It’s a warning, and there are measures you can take to avoid having data stolen.

The most important factor is your mindset. If you let down your guard, and many summer travelers do, you’re vulnerable.

Vacationers often conduct business on personal devices, and they use WiFi connections, such as those in airports, that are not secure. Or they check business email in hotel office centers equipped with computers that are equally unprotected.

What they don’t realize is that cyber criminals are often lurking nearby, waiting for these opportunities to steal data,

which they can accomplish in a matter of seconds.

Read more from

Local Governments

by Cyberattacks

Are Overmatched

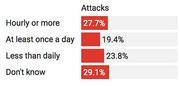

Source: University of Maryland, Baltimore County Get the data

In recent weeks, two major American cities had services disrupted by cyberattacks. A hacking attack in Baltimore disrupted online emergency dispatch services for nearly a full day. And Atlanta was hit with a ransomware attack that took city services offline for nearly a week.

These are the kinds of events that grab public attention, but research has suggested that the problem

is far larger than a few isolated events.

Local governments across the country are unprepared to prevent cyberattacks, and furthermore, they never identify who was responsible for the majority of those they detect, the research found.

Nearly half of those surveyed said they are attacked daily, but most don’t even record all of them.

The biggest impediment to improving cybersecurity is that local leaders have not made it a priority and have not demonstrated sufficient support for the IT and cybersecurity officials who filled out the survey.

Read more from theconversation.com.

NIST Updates its

Popular Framework

Credit: N. Hancek/NIST

In April, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released version 1.1 of the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure

Cybersecurity. It was an update of the first version of the voluntary guidelines NIST published four years ago at the direction of the Obama administration.

The organization announced these changes to the original:

Version 1.1 includes

updates on:

• authentication

authentication

and identity,

• self-assessing

self-assessing

cybersecurity risk,

• managing

managing

cybersecurity within

the supply chain and

• vulnerability

vulnerability

disclosure.

NIST also included a brief description of its methodology: “The changes to the framework are based on feedback collected through public calls for comments, questions received by team members, and workshops held in 2016 and 2017. Two drafts of Version 1.1 were circulated for public comment to assist NIST in comprehensively addressing stakeholder inputs.”

A New Model for

Cybersecurity

Investigations

Paul Rosenzweig

Shouldn’t someone investigate cybersecurity events to determine what happened, and how similar incidents might be prevented in the future? And with no effort to cast blame or judge whether the savings would justify

the cost?

There is an agency that already performs this function when there’s a plane crash: the National Transportation Safety Board. Why not use the NTSB as a model for an agency that would be tapped to investigate major cyber breaches?

This was the suggestion of Paul Rosenzweig, a senior fellow at the R Street Institute in Washington, D.C., who wrote a paper endorsing the idea, which he credited to Representative Denny Heck (D-Wash.). Rosenzweig, who also manages a small consulting company on cybersecurity and teaches at George Washington School of Law, suggested the new agency might be called the Computer Network Safety Board.

Read more from insidesources.com.

White House Axes

Cybersecurity Czar

In the 1960s, some writers of fiction publicly complained about the difficulty they had plying their craft because they found it impossible to compete with the reality

they were confronted by each day.

There are undoubtedly novelists today who feel the same way. But these days even journalists are finding themselves stretched in unusual ways. It can sometime be difficult to reconcile the competing realities we’re confronted by. And these can involve realities that bump into each other not only in different areas of the news, or different events, but sometimes even in the

same stories.

So, we have grown used to reading about the ever-expanding challenges of fending off cybersecurity risks. And preparing for the next new assault. And government agencies have tried hard to reassure businesses that they are doing everything they can to work with them against this growing threat.

And yet, at the very time that the Department of Homeland Security, which is generally viewed as the lead agency in defending against cyberattacks, was talking about the expanding risks, the administration eliminated the position of Cybersecurity coordinator on the National Security Council because

the role was no longer necessary.

Read more from csoonline.com.

It’s very difficult to treat an email that is sent from your U.K. office to an office in Brazil and is stored in the U.S. in compliance with any particular law.

The GDPR requires a cultural shift in the way that people think about privacy. And that kind of approach, or something like it, is what’s going to be needed in the U.S.

art Huffman is a partner in Reed Smith’s IP, Tech and Data Group. Given his expertise

in privacy and information security, it almost goes without saying that he’s been advising clients about the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). And there’s a lot to talk about, especially concerning the need for companies to focus on their third-party suppliers. Huffman also sees U.S. companies adopting the EU’s approach globally. For practical reasons alone, it makes sense. This is Part One of an interview that will conclude next month.

Legal BlackBook: When did you first start advising clients about the GDPR?

Bart Huffman: The GDPR was first published in May of 2016. I would say that the first client inquiries came a few months afterward. There was a big push in the middle to the end of 2017. It’s been a year now that it’s been pretty consistent, and in the last few months there’s been a flurry of activity for a lot of clients who didn’t realize that they might be impacted.

LBB: For companies that have a substantial customer or employee base in Europe, how much time has it taken for them to prepare for the new regulation?

BH: For any large organization with a significant number of data subjects in the EU—either consumers or employees—probably a year is required. But in part that depends on the buy-in that you get from upper management. There’s often a ramp-up period to convince management of the significance of the effort.

FLORIDA ADOPTED MANDATORY CLEs IN TECH.

WHERE ARE THE FOLLOWERS?

Most states agree that lawyers must be competent in this area,

but training is optional.

Cybersecurity and data privacy are viewed as the most important areas of instruction.

John Stewart

few years ago, the Florida State Bar decided that it was time to affirm that lawyers have an obligation to demonstrate

competence in understanding and using technology. It was an opinion that the American Bar Association and many states had already adopted, so there was nothing startling about this. But Florida did not stop there. It took the next step: It added a requirement that at least three of the 33 hours of CLE training that its lawyers are required to complete within three years be instruction on technology.

The wonder is that Florida was the first state to do this. And 18 months later, no other state has yet joined it (though two seem close).

The funny thing is that the Florida lawyers who pushed this through didn’t set out to lead the pack. They were just trying to catch up. But once they did the required homework, that next step seemed obvious. And not because they were technophiles.

John Stewart was the lawyer selected by the Florida Bar’s Board of Governors to chair the technology subcommittee that studied the issue. But he would never call himself a techie. “I think I was tapped because I was the youngest member of the Board of Governors, not because I was necessarily the most technologically savvy,” said Stewart, who is now 48.

But he did have impressive organizational skills. A partner at Rossway Swan Tierney Barry Lacey & Oliver in Vero Beach, Stewart had chaired committees on topics ranging from communications to alternative dispute resolution to gender bias and diversity. And it didn’t take the technology committee too long to see the importance of their work. “It was a slow build, but then there was sort of an awakening,” Stewart said.

When the Florida group got started in 2013, the ABA’s Commission on Ethics 20/20 had already weighed in a year earlier. “Technology has irrevocably changed and continues to alter the practice of law in fundamental ways,” the commission wrote. “Lawyers must understand technology in order to provide clients with the competent and cost-effective services that they expect and deserve.”

In Florida, they could see its influence in the proliferation of small firms. About three quarters of the Bar’s 105,000 members practiced in firms with 10 lawyers or fewer; 65 percent in firms of five or fewer. Many were delivering services “almost exclusively online,” Stewart said.

About a third of the country’s state bar associations had already adopted language similar to the ABA’s, Stewart recalled. It seemed time for Florida to wake up and smell the coffee. But if they were going to change the language on competence, “we better offer them education, too,” Stewart said, explaining the committee’s reasoning. “We didn’t want to force that obligation on them and then not give them the resources to meet it.”

Within its first year, Stewart’s committee was convinced that some sort of lawyer education was necessary. But the members wrestled with the details. Should it be mandatory, “or more “aspirational”? How many hours should they recommend? And should they prescribe subjects, or leave that open-ended?

They decided that if they were going to recommend the change in language, they ought to back it with mandatory training. They proposed boosting the 30 hours of CLE courses to 36 over three years, with the extra six devoted to tech.

The Board of Governors did not embrace their proposal with unanimously open arms. Put any group of lawyers in a room, Stewart said, and there’s always dissent. One board member solicited feedback from the Bar members he represents, and they rejected the idea. “Younger lawyers say, ‘We already know this,’” the board member told The Florida Bar News. “The older lawyers say, ‘I hire people to do it.’”

After kicking the plan around, the board voted in July 2015 to cut the proposed six hours in half and adopt the new language, along with three hours of mandatory education in tech. The proposal was then sent to the state Supreme Court, which made it official in September 2016. The rules took effect the following January.

Since then, Stewart said, he hasn’t heard any complaints. And lawyers have been voting with their feet. Many more signed up for technology CLEs than had been anticipated. The publicity probably helped, Stewart acknowledged, but he suspects that lawyers have begun to “understand the value to their practices.”

Stewart added that cybersecurity and data privacy are probably the most important areas of instruction. “One of the key core values that distinguishes the legal profession from others,” he said, “is that we are obligated by law or by rule to keep client confidences.” And when lawyers fail, he noted, “it’s almost always unintentional. Which is why this CLE has become so valuable.”

So, if Florida finds it so valuable, and nearly every other state has affirmed the importance of technology in the profession, why have all the other states remained on the sidelines?

Stewart has no answer—except to note that the state bars of North Carolina and Pennsylvania have now proposed that their own supreme courts adopt mandatory CLE training in tech.

Does he think that this is the beginning of a trend? Has momentum finally shifted? He doesn’t have a clue, Stewart said. He has no insight into the workings of other states. But he feels good about the progress Florida has made. And in the process, he’s learned a lot. “I’ve certainly grown to appreciate technology,” he said.

Cybersecurity

Tips

t’s reached the tipping point. Recently I had dinner with friends

who had no connection with the law, and they were the ones who brought up the GDPR. They weren’t quite sure about the letters, or the order, and they weren’t sure what it stood for. But even after I said “General Data Protection Regulation,” they still wanted to talk about it. And they had lots to say about privacy.

For those of us who have been living with those letters, we’re only just out of the starting gate. But already it feels as though

we’ve been overloaded. And yet... when we interviewed Reed Smith partner Bart Huffman, an expert on privacy and security, it didn’t feel that way at all. In fact, he covered so much information that struck us as essential reading for lawyers that, rather than edit it down, we decided to publish Part One in June (Culture Shift, Courtesy of Europe) and Part Two in July.

Another article is about the opposite of a tipping point (call it the ticking point). Eighteen months ago, Florida became the first state in the country to mandate tech training for lawyers. But since then, not one state has followed Florida’s lead (Florida Adopted Mandatory CLEs in Tech. Where Are the Followers?).

A subject we return to often in this publication is how and when companies decide to cooperate with the government when they’re dealing with breaches. Kimberly Peretti discusses this issue, and, as a former senior litigator at the U.S. Department of Justice, she passes along four tips suggesting how companies can maximize the benefits of cooperating (Working With the Government After a Breach).

LBB: What has been the hardest part of preparing?

BH: A lot of companies don’t realize what personal data they process. They may know pieces of what goes on, but in order to approach the GDPR appropriately, one of the first steps is to get your arms around exactly what data you process, what third parties you use to process it, where the data is located, etc. Everything else falls from that.

LBB: What is the role of in-house lawyers in this process?

BH: Usually in-house lawyers will be part of a team that is put together to work toward compliance. But it has to be a team. In-house counsel certainly can’t do it on their own. They can help guide the effort from a legal perspective, in terms of the actual requirements and regulations, and they can help pull together the various team members, but there are multiple operational, compliance and governance issues at play. Sometimes there’s a project manager along with the legal counsel, and sometimes the legal counsel will serve that function as well. I think they’re critical to the effort. Compliance with the GDPR is significant from a number of different perspectives, reputationally as well as potentially financially, given the penalties that can be involved.

LBB: Can you compare the GDPR to the U.S. rules on privacy?

BH: The U.S. continues to evolve much the way it has over the past few decades. We see states being a little more proactive in terms of legislation on things like biometric data, and they continue to be active in the data breach response area, which focuses on personally identifiable information. While popular opinion has continued to swell around appropriate handling of personal information, we haven’t yet seen any comprehensive privacy legislation make its way too far.

LBB: So the GDPR is a more up-to-date approach to data privacy than the U.S. model?

BH: I believe so. The nature of processing today is very complex and not readily ascertainable by an individual, nor is it necessarily understandable by an individual who’s not skilled in internet systems. So the notion of accountability is essential, since the consumers can't individually control or make decisions about how their data is used. Especially when data is not being controlled just by people anymore—increasingly, it’s also being processed at the direction of algorithms in the context of artificial intelligence. So the GDPR puts into place this notion of accountability that the processor of the data has to be prepared to demonstrate: compliance with fundamental fair principles of processing. You can’t just rely on the consumers.

LBB: What about vendors and service providers? Does a company need to ensure that vendors are in compliance with the GDPR as well? And if they’re not, could a company be held liable for the failures of its vendors?

BH: Absolutely. That’s very much the case under the EU system and under the U.S. system, traditionally. The primary data custodian—referred to in the EU as the data controller—has ultimate responsibility for processing personal data, and a lot of the requirements imposed on the vendors flow from that. So, for example, the data controller under EU law must keep records and be able to demonstrate compliance. And obviously they can’t do that if their vendors don’t also keep records. Data controllers must notify data subjects of breaches. And, of course, they can’t do that in every case if the vendors don’t notify them of breaches when they occur. So a lot of the requirements just flow naturally from the fact that the controller is ultimately responsible.

LBB: That would seem to be a big issue for many companies, because there’s growing evidence—as we’ll see in another article we’re running this month—that companies are not always clear on how involved they need to be in auditing and monitoring their vendors. Is that something you’re concerned about, and that you talk about with your clients?

BH: Yes, this is a classic task for any data controller or data custodian. There are three aspects to handling vendor relationships appropriately with respect to personal data—and, frankly, it also applies to other confidential data. You’ve got to have diligence on the front end. You’ve got to have contractual protections. And then you’ve got to have some method of reasonable oversight or validation. And that series is baked into requirements even in the U.S., going back to the Federal Trade Commission’s Safeguards Rule under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. It certainly is the case in the GDPR that that is expected of the controllers. Both the first and the last of those three aspects involve assessment of what risk is presented by a given vendor’s processing of data. The effort that goes into auditing or requiring reports from the vendor should be proportional to the risk associated with the processing.

LBB: Are there other tricky areas involving privacy that companies and their general counsel should be thinking about, but may not be?

BH: There are a number of stages to compliance. As I mentioned earlier, the first part of the exercise is to get your arms around exactly what personal data processing you do, and which parts of that data processing fall within the scope of the GDPR or other privacy law. Once you do that, there are different buckets to think about. For instance, take processor agreements under the GDPR. Those have to be buttoned up and complied with under Article 29. There’s the issue of data transfers. If you’re transferring data out of the EU, you’ve got to think of the requirements under Chapter 5. If you’re handling any sensitive data, you are faced with default prohibitions under Articles 9 and 10. Interestingly, sensitive data is defined differently in the EU, because they don’t have as much of a focus on identifiers. The EU focus for sensitivity has its roots more in anti-discrimination: things like race, ethnic background, religious affiliation, philosophical beliefs, association in trade unions. And underneath it all, you’ve got to comply with the fundamental principles of appropriate handling of personal data, and you have to make sure that you have a basis for processing the data to begin with. As a comprehensive scheme, the GDPR requires personal data protection to be taken into consideration from a number of different perspectives, both internally and in processing arrangements that involve third parties.

LBB: While the GDPR was about to roll out, we had the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal explode in the media, further exposing the shortcomings of the way that U.S.-based companies handle customer data. Do you think that’s likely to spur legislation? There’s been talk.

BH: There continue to be spikes of interest within the public that are centered around big events, going back to the Target breach, when consumers started to get much more anxious about payment card data, and companies started to get much more careful about third-party service providers. Also, there was the Sony breach, where everyone woke up to the fact that not only might the cyber criminals get in and steal your personal data, but they might get in and set your house on fire, take all of your IP assets and shut down your communication systems. The Equifax breach was another major event, and then of course we’ve had Facebook. I think there will continue to be a lot of good thought around the need for privacy legislation, but we have yet to see anything concrete and comprehensive in the U.S. I think there will be a lot of learning from the fact that so much of American business is focused on the GDPR, and the GDPR requires a cultural shift in the way people think about privacy. And I think that that kind of approach, or something like it, is what’s going to be ultimately needed in the U.S., but it’s probably a little ways down the road.

LBB: it seems that some companies have already recognized that the GDPR applies to them and is superior to what we have in the U.S., and they’re taking steps to adopt it globally. Do you have a sense of how popular that approach is now?

Do you think that’s likely to catch on?

BH: I think it is likely to catch on, for several reasons. One is that there has been this explosive growth in the privacy profession in general. The International Association of Privacy Professionals membership has grown, year over year, by astounding levels. Privacy professionals continue to get certified, and there’s a real demand for them now, especially in Europe. So there are a lot more people thinking about privacy, and a lot more people skilled in working with privacy matters. That has a strong influence on its own. The other reason is that there are numerous privacy laws being enacted around the world—in Japan and Australia, for example—that are going to have an impact. Starting a few years ago, companies began to realize that they need to embrace a global privacy platform, because it is going to be hard to comply with all of these various requirements by segregating data and treating the data differently. It’s very difficult to treat an email that is sent from your U.K. office to an office in Brazil and is stored in the U.S. in compliance with any particular law. You really have to have a baseline standard that’s calculated to meet the best practices and the essence of the various laws involved.

LBB: Is this something you recommend?

BH: To the extent that companies can do it, they should definitely be thinking about that. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense from an economic perspective, because there are restrictions associated with the use of data that can be problematic for U.S. businesses. For example, the spam laws in the EU are fairly strict compared to those in the U.S. We have pretty much an opt-out basis for commercial email, but in the EU, the existing opt-in approach is going to become more ingrained, and that can put a serious impediment on the ability to communicate even with business contacts—and certainly with consumer contacts—in the way that most people do today with email.

LBB: On a personal note, I recently organized my high school reunion, and I realized that my classmates wanted to be in touch with each other. But because I’ve spent a good deal of time focusing on privacy issues, I also decided that I didn’t want to unilaterally give out email addresses to the larger group without individuals’ opting in. Some of them appreciated that. Some of them didn’t get it, or hadn’t read my explanation and didn’t understand why I’d excluded their addresses from the list I sent out. But the idea of opting in seems like an important thing to recognize now.

BH: I think that’s right. And it’s interesting that some people appreciate this. That’s another important point worth thinking about, in terms of companies adopting GDPR-like thinking. The winners in this effort are going to be those that are able to demonstrate value and creativity, in terms of their privacy practices and the choices and preferences that they offer their customers and the people they communicate with. Like you say, giving someone an opt-in has value. It adds value not only in terms of the appreciation of the individual, but also in terms of the quality of your data, your contact list. Even in the U.S., absent the law, an opt-in database is sometimes required by email marketing companies because they don’t like to send spam. Another requirement of the GDPR that we haven’t spoken about is transparency, which is an essential requirement. And transparency under the GDPR means really communicating to data subjects how their data is collected and used, and for what purposes—and doing that in a way calculated to actually inform them. So you have privacy engineers working hard on ways to appropriately advise people, or in some cases even nudge them, about their privacy rights and choices. The old boilerplate privacy policy is going to become something of the past. And I believe that people will appreciate that the same sort of advanced thinking that has moved information technology is increasingly being applied to advance the means and usefulness of informing people, and giving them choices about the use of their personal data.

Next month, in Part Two of this interview, Huffman will talk about the right to be forgotten and other tricky features of the GDPR that have lawyers wondering how it will all play out.

Finally, the article we lead with in this issue is an interview with the Association of Corporate Counsel’s chief legal officer, Amar Sarwal, who digs into ACC’s recently released State of Cybersecurity Report—its first in three years (Cyber Survey Underscores Dour Perspective of In-House Lawyers).

What’s particularly valuable about this report is in the subtitle: an in-house perspective. The survey reveals what these lawyers are experiencing, and some of the most interesting data reflects not just what they know, but what they don’t.

Sarwal takes an unflinching look at a pretty grim landscape and delivers a lucid analysis. It’s one of his skills that we have come to appreciate during his eight years at the organization. By the time you read this, however, he will have departed from his post there for a job closer to home. Literally. We hope he’s appreciated at his new work place. We wager that his old one will find him hard to replace.

DOUR PERSPECTIVE

OF IN-HOUSE

LAWYERS CAN'T HELP STRATEGIZE

ABOUT SOMETHING THAT THEY DON'T KNOW

WHAT THE NUMBERS SAY

In-house lawyers' responses when asked how often their

companies conduct vendor security audits.